WASHINGTON:

The United States has announced that the export-control systems of Australia and the United Kingdom are now deemed comparable to those of the US, a critical development for the AUKUS defence pact. This determination, conveyed by the US State Department to Congress on Thursday, paves the way for enhanced technology sharing among the three nations, a key component of the AUKUS agreement.

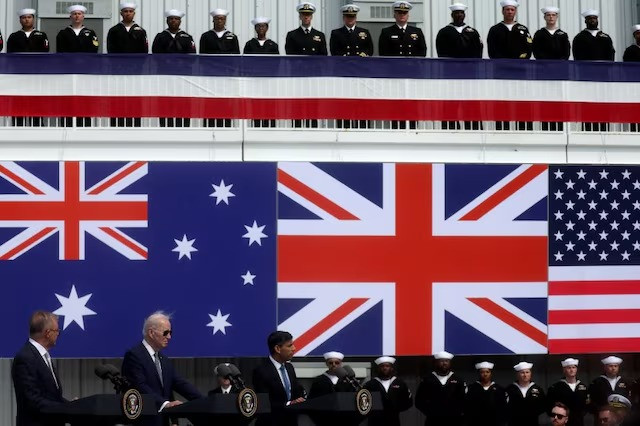

AUKUS, established in 2021, was designed to counterbalance China’s rising influence by enabling Australia to acquire nuclear-powered attack submarines and other advanced military capabilities, such as hypersonic missiles. However, strict US regulations under the International Trafficking in Arms Regulations (ITAR) had posed significant challenges to the sharing of sensitive technologies among the pact’s members.

The 2024 US National Defence Authorisation Act (NDAA) required President Joe Biden to assess whether Australia and the UK had export-control regimes equivalent to those of the US, a condition for granting ITAR exemptions. The State Department’s recent determination that both countries meet this requirement is a significant milestone in advancing the AUKUS partnership.

In a statement, the State Department revealed that it will publish an interim final rule to amend ITAR, implementing export licencing exemptions for Australia and the UK starting on 1 September. However, this rule will include a list of sensitive technologies that remain excluded from these exemptions, which analysts warn could still pose bureaucratic obstacles to the realisation of AUKUS projects.

Despite these potential hurdles, the announcement has been met with optimism. Australian Defence Minister Richard Marles described the reforms as a “generational change,” while the UK government hailed the move as a “historic breakthrough.” Marles emphasised that these reforms would revolutionise defence trade, innovation, and cooperation, enabling collaboration at a scale necessary to address current strategic challenges.

A US State Department official highlighted that approximately 80% of the value of current commercial defence trade with Australia would be covered by the new licensing exemptions, significantly improving the speed and predictability of transactions. Historically, the US has issued around 3,800 defence export control licences annually for Australia, with approval processes taking up to 18 months. In contrast, approvals for the UK have taken around 100 days.

Under the new rules, the US State Department will have a 45-day window to decide on technology transfers on the excluded list between governments and industry, and 30 days for government-to-government transfers. A 90-day public comment period for the interim rule will also allow for further refinement.

The aim of these changes, according to the State Department, is to “maximise innovation and mutually strengthen our three defence industrial bases by facilitating billions of dollars in secure, licence-free defence trade.” However, the final rule’s effectiveness will depend on how administratively burdensome the ITAR waivers prove to be.

The draft rule, first unveiled in April, was initially celebrated as a potential game-changer by Australia, though some defence experts expressed concerns that the broad exclusion list might render the policy changes ineffective. The updated list of exclusions still includes certain submarine and undersea acoustics technologies, crucial to AUKUS, but officials emphasised that these could still be exported with the appropriate licences processed within the designated timeframes.

Republican Congressman Michael McCaul, Chair of the US House Foreign Affairs Committee, welcomed the recent developments but cautioned that too many critical items remain excluded, which could hinder the full implementation of AUKUS. He called for the Excluded Technologies List to be significantly narrowed to ensure that government regulations do not impede the alliance’s ability to effectively deter conflicts in the Indo-Pacific region.

Jeff Bialos, a former senior Pentagon official, echoed this sentiment, noting that the success of the ITAR waivers will hinge on their administrative practicality. If the process becomes too cumbersome, it could undermine the intended goal of enhanced technology cooperation within the AUKUS framework.