Gujarat Under Modi: Laboratory of Today’s India

By Christophe Jaffrelot

Liberty Publishing

ISBN: 978-627-7626-50-1

546pp.

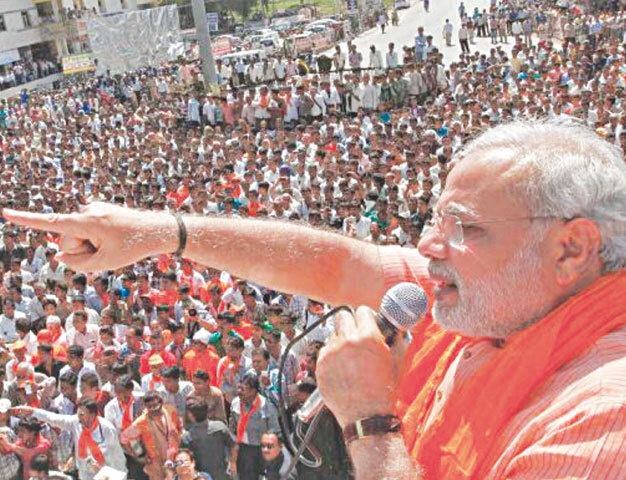

An extensively researched book by Christophe Jaffrelot, a French political scientist specialising in India and Pakistan — Gujarat Under Modi: Laboratory of Today’s India — deals with the transformation of Gujarat into “a laboratory of Hindu nationalism.” Narendra Modi served as chief minister of Gujarat for a record 13 years between 2001 and 2014, after which he became the prime minister of India.

Jaffrelot has written extensively on India and Pakistan and is considered a formidable scholar on the region. Other books by the same author include: India’s First Dictatorship: The Emergency 1975-1977 (2020), Modi’s India: Hindu Nationalism and the Rise of Ethnic Democracy (2021), The Pakistan Paradox: Instability and Resilience (2015), Religion, Caste and Politics in India (2010), A History of Pakistan and its Origins (2002), and his doctoral thesis published as The Hindu Nationalist Movement In India (1996).

Gujarat is a unique state in many respects, including “its extreme valorisation of an economic ethos, its caste hierarchies and its relationship with Islam… these characteristics are largely due to geography.”

Gujarat is the fifth-largest state in India and the ninth most populous, with a population of approximately 60 million. It has the longest coastline of 2,340 kilometres, neighbouring Pakistan. Muslims started arriving there soon after the advent of Islam in the seventh century.

A well-researched book by a well-known French scholar argues that Indian PM Narendra Modi used his rule in the state of Gujarat to establish the principles for his Hindutva vision of India

Moreover, referring to Gujaratis, the director of entrepreneurship development of Gujarat declared in 2013, that “Entrepreneurship is in their blood. No doubt in that, as Gujarati children are exposed to money-making businesses early on. Even in social gatherings, people talk about business rather than bureaucracy, politics or literature. By the time a person comes out of college, he would have a role model in one or another successful businessman.”

Jaffrelot remarks that: “The elite of Gujarat are represented by two poles, the martial Rajputs and the mercantile Patels.” Consequently, he highlights five pillars of Modi’s politics, the first of which is communal polarisation. It is not a new approach, though it reached an unprecedented scale under Modi. While this polarisation had traditionally been fostered by Hindu-Muslim violence, in 2002 it resulted from unprecedented atrocities that raged for two months, leading to the second largest number of Muslim deaths since Partition.

“That the BJP could win state elections in this very specific context, whereas it had faced several electoral setbacks since 2000, showed that it ‘worked’ politically, as BJP leaders in the state had anticipated.” It remained a major factor in the government’s strategy subsequently.

The de-institutionalisation of the rule of law was the second weapon of Modi’s politics. “Policemen who took part in anti-Muslim violence [in Gujarat] were rewarded, and the government ensured that a proper judicial investigation would not be pursued… rule of law was damaged in many other ways and for other reasons under Modi.”

The third pillar was socio-economic policies. Gujarat is known for its industrial dynamism, and investors were attracted to the state in a big way. “Instead of capitalising on the Gujaratis’ sense of entrepreneurship, which had given birth to a dense network of SMEs [small- and medium-sized enterprises], Modi promoted big projects by wooing large Indian companies. In return, some of these businessmen, including Gautam Adani, supported Modi. The Modi government invested more in infrastructure — roads, ports and energy — than in development expenditure, including health and education.”

The fourth was Modi’s style. He portrayed himself as an embodiment of Gujarat against the Centre and the Nehru-Gandhi family. “These techniques also allowed him to relate directly to voters in a new form of high-tech populism… Modi gradually captured all power within the government and his party… by relying on the bureaucracy [after promoting civil servants who eventually became part of the core group of Gujarat’s administration] and by relating directly to the people.”

The fifth pillar of Modi’s politics was gaining and exerting domination over supporters, opponents and victims. Part Five of the book focuses on the social and political context that has enabled Modi’s rise and the consequences of his rule for Gujarat society.

Jaffrelot points out “how the BJP started to grow at the expense of Congress when the party capitalised on new developments, [such as] the saffronisation of the upper castes and Patels, who resented [former Gujarat chief minister] Madhavsinh Solanki’s ‘reservation policy’ in the 1980s. This core group of supporters — which partly coincided with Gujarat’s middle class — remained staunchly behind the BJP in the 1990s.

“But during his terms, Modi added the… ‘neo-middle class.’ This group of aspiring Gujaratis was mostly made up of people who, like him, came from the lower castes, had migrated to urban centres, and wanted to benefit from the state’s economic growth. Modi’s political strategy relied on social polarisation in the sense that not only the rural part of the state was neglected but, in the urban context, the poor were marginalised, with the result that cities became ‘bourgeois at last’.”

The author has documented detailed accounts of extrajudicial killings, confessions of rioters who attacked Muslims and trials after racial violence in Modi’s Gujarat, along with crime statistics based on region, religion and other classifications. There are 25 pages of informative socio-economic statistical charts appended in this book.

In 2017, the Pew Research Centre conducted a survey in 34 countries to measure “pro-democracy attitudes” as well as “openness to non-democratic forms of governance, including rules by experts, a strong leader or the military.” Commenting on the results, the Pew team pointed out that “support for autocratic rule is higher in India than in any other nation surveyed” and “India is only one of four nations where half or more of the public supports governing by the military.”

Jaffrelot has built a convincing and thorough case for his original premise that Gujarat was indeed Modi’s laboratory for today’s India, as illustrated by his subsequent rule as prime minister of India.

The reviewer is a freelance writer and translator. He can be reached at mehwer@yahoo.com

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, January 4th, 2026